I Built a Truth Serum for AI Models (And Learned They Argue Like Consultants)

Over the weekend, I did something probably unnecessary but deeply satisfying: I built an app that runs the same question through 8 leading LLMs and makes them bet on each other’s answers.

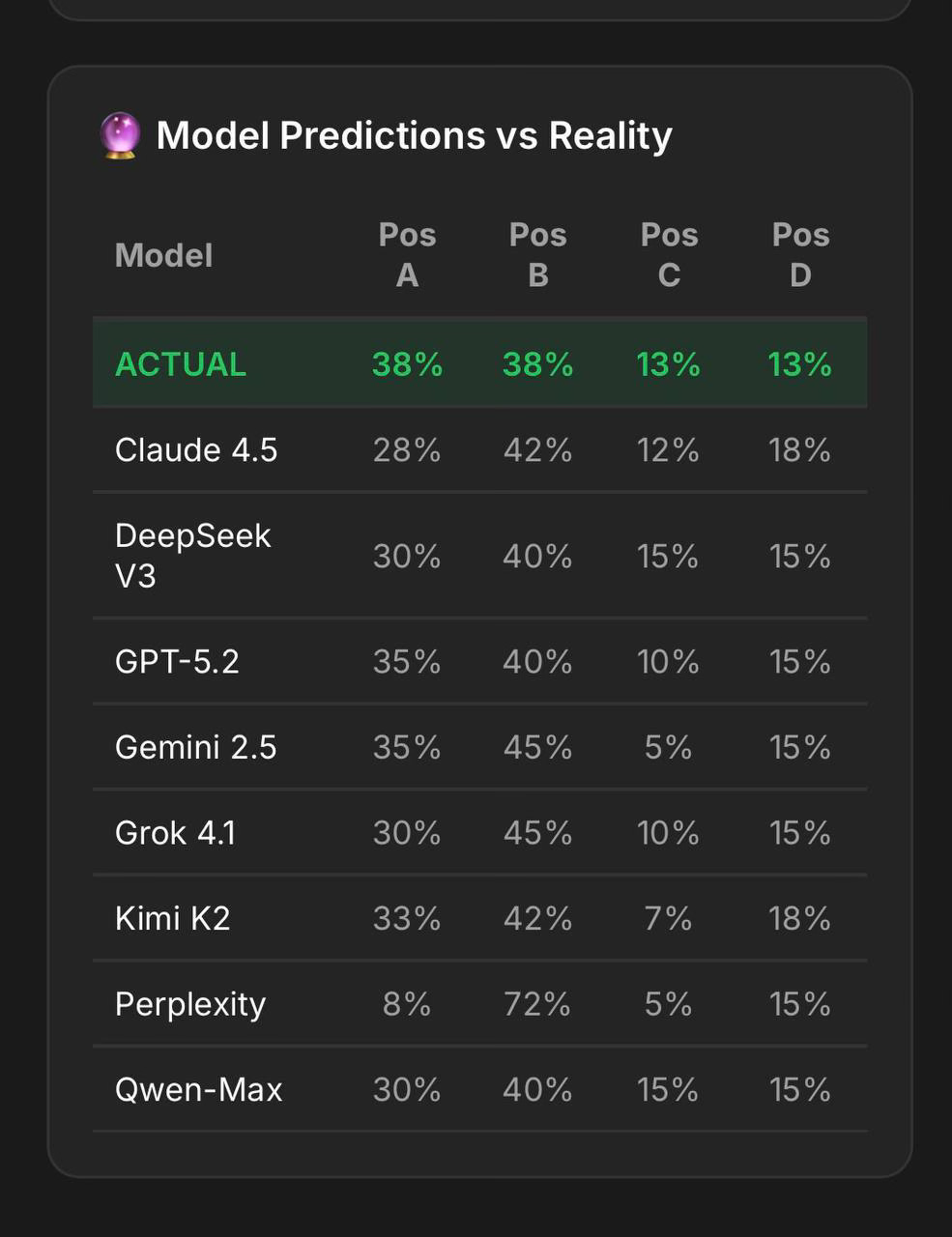

Here’s how it works: I give all eight models - Claude 4.5, GPT-5.2, Gemini 2.5, Grok 4.1, DeepSeek V3, Qwen-Max, Perplexity, and Kimi K2 - the same question. They each answer it. But here’s the twist: I also ask each model to predict what the others would answer.

Then I run everything through Bayesian Truth Serum

(BTS), a statistical method that finds the most likely true answer not by looking at what’s most popular, but by finding what’s surprisingly frequent - answers chosen more often than the models themselves predicted.

I threw 72 questions at them, covering everything from business strategy and SEO to medical ethics and philosophy. The Gemini 2.5 PRO bill made me wince, but what I learned about how these models think was worth it.

The Logic Is Beautiful (and Very Human)

The genius of BTS is that it exploits a fundamental truth about deception: lying is easy, but predicting how others will lie is nearly impossible.

Think about it. If I ask you a factual question you’re unsure about, you might guess wrong. But if I also ask you to predict what answer your colleague would give, and then what their colleague would give, suddenly the layers of uncertainty compound. The truth has internal consistency; lies don’t.

This is exactly how interrogators work, by the way. They don’t just ask “what happened?” They ask: “What do you think your partner told us? What would your boss say if we asked him? How would the security footage look?” Liars struggle with these nested predictions because they have to simulate increasingly complex false narratives.

We essentially forced the models not just to answer, but to place bets on each other. And those bets revealed more than the answers themselves.

What I Found: AI Models Have Personalities (And Blind Spots)

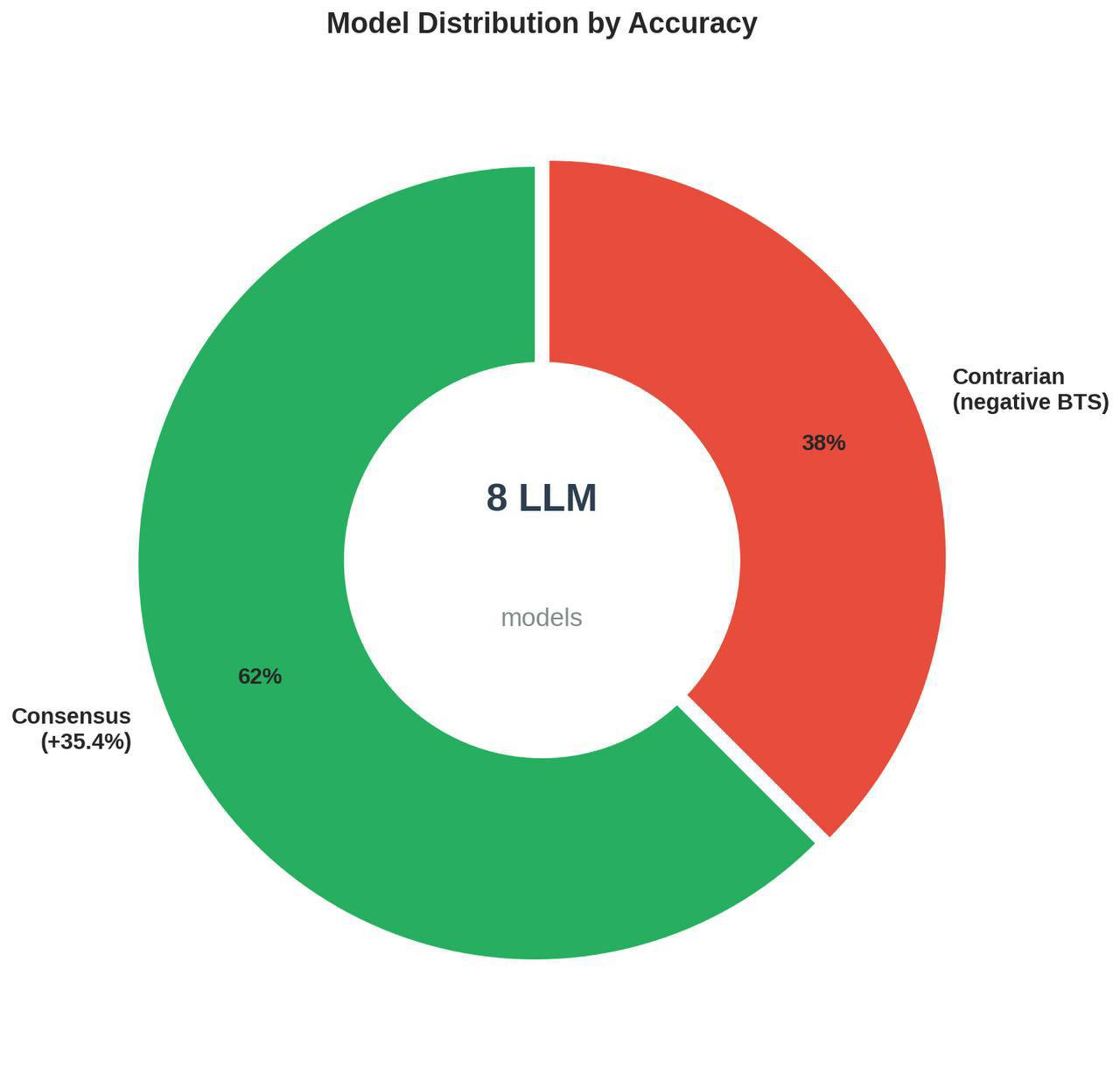

After running 72 questions through this gauntlet, clear patterns emerged. The models sorted themselves into two distinct camps: the Consensus Builders and the Systematic Rebels.

The Consensus Builders - Gemini 2.5, Grok 4.1, Claude 4.5, DeepSeek V3, and Qwen-Max - consistently landed in the statistical sweet spot of “surprisingly frequent but not obviously popular.” These are your reliable experts. When they agree, you can usually trust them.

But each one gets there differently.

Claude is the classic business analyst. Ask it anything and it immediately starts mapping structures, identifying risks, and building frameworks. It’s the consultant who walks into a meeting and starts drawing boxes and arrows on the whiteboard. Always cautious, always systematic, always asking “but have we considered the downside?”

Grok is the aggressive practitioner. It loves numbers, ROI calculations, and cutting through bullshit. Where Claude builds frameworks, Grok builds spreadsheets. It’s the CFO who interrupts your strategy presentation to ask “okay but what’s the actual payback period here?”

GPT-5.2 is the systems architect. It thinks in platforms, ecosystems, and long-term infrastructure plays. Amazing for big-picture thinking, but sometimes too abstract when you need to know what to do tomorrow. It’s the person who responds to “we need to fix this bug” with “well, really we should rebuild our entire architecture.”

Then there are the Systematic Rebels: Perplexity, GPT-5.2 (yes, it plays both roles), and Kimi K2.

These are the models that consistently go against the grain. They’re the employees who, in every meeting, raise their hand and say: “Okay, but what if we’re looking at this completely wrong?”

And here’s the thing: you need them.

Why Being Right Isn’t Enough

I wrote once about how being right is only half the battle. The real challenge starts when you need to convince others to accept your point of view, especially about strategy you’ve built from experience and deep knowledge.

Watching these models interact taught me something about this dynamic.

The Consensus Builders are usually right, but they’re right in predictable ways. They’ve internalized the same training data, the same patterns, the same conventional wisdom. They’re excellent at navigating known territory.

The Rebels? Their answers need double-checking. Sometimes they’re confidently wrong. But they’re also the ones who surface blind spots, who ask the questions everyone else assumes, who suggest the approach no one else considered.

From my experience the most dangerous projects aren’t the ones where everyone disagrees - those force healthy debate. The dangerous ones are where everyone nods along to the same flawed assumption because it sounds reasonable and no one wants to be the contrarian.

This is why I always want at least one Perplexity in the room - someone constitutionally incapable of just going along with consensus.

The Practical Question: Which Model Should You Use?

Here’s where people always trip up. They want to know: which model is “the best”?

Wrong question.

The right question is: which model is best for this specific task?

If I’m building a business case that needs to survive CFO scrutiny: Grok. It’ll find the holes in my logic before the finance team does.

If I’m designing organizational change and need to map out all the stakeholders, risks, and contingencies: Claude. It won’t let me skip steps or ignore political realities.

If I’m thinking about platform strategy or long-term technical architecture: GPT-5.2. Just don’t expect tactical next steps.

But if I want to stress-test an idea? I run it past Perplexity or Kimi. They’ll poke holes I didn’t see coming. Half of what they say will be wrong, but the other half will save me from expensive mistakes.

The Real Lesson: Diversity of Thought Isn’t Optional

Running this experiment crystallized something I’ve learned over years of implementations: you cannot solve complex problems with a single perspective, no matter how “right” that perspective is.

I’ve seen enterprise software selections where everyone chose the “obviously correct” platform, and then spent two years fighting it because no one asked the contrarian question: “What if our process doesn’t actually fit this model?”

The Bayesian Truth Serum approach works because it exploits something fundamental: truth has a different statistical signature than consensus. Sometimes the right answer is surprising. Sometimes it contradicts what the experts agree on.

But you only find it if you’re willing to collect multiple perspectives, including the uncomfortable ones, and then apply rigorous thinking to sort signals from noise.

How to Build Your Own Truth Serum

You don’t need to code an app or pay for Gemini 2.5 PRO API calls to use this principle.

Here’s what actually works:

1. Ask multiple models the same question. Not as a way to pick the “best” answer, but to understand the range of perspectives. Where do they agree? Where do they diverge? Why?

2. Pay special attention to the outliers. When one model gives you a radically different answer, don’t dismiss it. Dig into why it’s different. Sometimes it’s wrong. Sometimes it saw something the others missed.

3. Force models to explain each other’s reasoning. Take Claude’s answer and ask GPT: “Why might someone give this response? What assumptions are they making?” Then reverse it. This is the manual version of what BTS does automatically.

4. Use consensus as a starting point, not an endpoint. When all models agree, you’ve probably found conventional wisdom. Which is often correct! But not always. The consensus said blockchain would revolutionize everything, remember?

5. Keep your rebels close. Whether it’s an AI model or a human colleague, the person who consistently disagrees with everyone else is either a fool or seeing something important. Your job is to figure out which.

The Meta-Lesson

The most interesting finding from my weekend experiment wasn’t about AI models at all.

It was watching how my own confirmation bias kicked in. When the models agreed with my existing views, I immediately thought “see, the AI gets it.” When they disagreed, my first instinct was “well, the models don’t have full context.”

This is exactly what the BTS method is designed to counteract. It removes my judgment from the equation and asks: statistically, based purely on the pattern of answers and predictions, what’s most likely true?

Sometimes the answer aligns with what I wanted to hear. Sometimes it doesn’t.

Both are valuable. But the second type is more valuable, because it’s the only kind that actually teaches you something.

So What Am I Going to Do With This?

For now, I’m using this setup as a personal advisory board. Before I publish something, before I make a recommendation to a client, before I commit to a strategy - I run it through the gauntlet.

Eight different perspectives, forced to bet on each other, statistically analyzed for truth content.

Is it perfect? No. Will it stop me from being wrong? Definitely not.

But it will make sure that when I’m wrong, it’s because I ignored multiple warning signs, not because I never asked the question in the first place.

And in a world where being confidently wrong has never been easier, that feels like progress.

If you’re interested in the technical details of the Bayesian Truth Serum method, or want to see the full breakdown of how different models performed across question categories, let me know.

Here is my LinkedIn