The Hidden Cost of Overcoaching: Why Less Instruction Creates Better Athletes

I recently read a study about how and when coaches should give feedback to athletes.

The idea that particularly caught my attention was the phenomenon of overcoaching.

Too frequent and direct instructions hinder development because the athlete stops listening to themselves, relying on their own sensations, and seeking solutions in a dynamic environment.

In business, especially in sales or consulting, this is encountered everywhere.

When a manager literally spoon-feeds every task or gives direct comments and instructions too often, the space for creativity disappears.

As a result, the employee does things seemingly correctly, but without energy, without an internal sense of the outcome, and often not what’s actually needed. This is emotionally draining and reduces effectiveness.

The article also emphasizes: good training is built not on the quantity of feedback, frequency, and precision, but on the design of the situation.

In other words, you create conditions where a person naturally receives feedback themselves - through results, client reactions, the market.

The leader’s role here isn’t to solve the problem for the subordinate, but to set the framework, sometimes use a metaphor or question, and give them a chance to search independently.

Another important observation: coaching heavily depends on personal compatibility.

Even the most experienced and emotionally mature people can’t always be good coaches for everyone.

Like in sports: one person needs a tough mentor, another a partnership style.

Therefore, there’s no universal approach. What really matters is the balance between support, freedom, and personal chemistry.

What the Research Actually Shows

The academic paper I’m referring to comes from sport psychology researchers who developed what they call a “Skill Training Communication Model” specifically for understanding when and how coaches should provide feedback to athletes.

The researchers identify a critical problem: traditional coaching approaches often rely on prescriptive, corrective verbal instructions - essentially telling athletes exactly what to do and how to do it. This approach, while seemingly helpful, can actually impede development by restricting the athlete’s own exploration and problem-solving abilities.

The mechanism is fascinating. When coaches provide too much explicit, detailed feedback, especially immediately after a performance, they interfere with the athlete’s intrinsic feedback systems. Athletes need time and space to perceive information from their own movements, to feel what works and what doesn’t, and to self-organize functional solutions to performance problems.

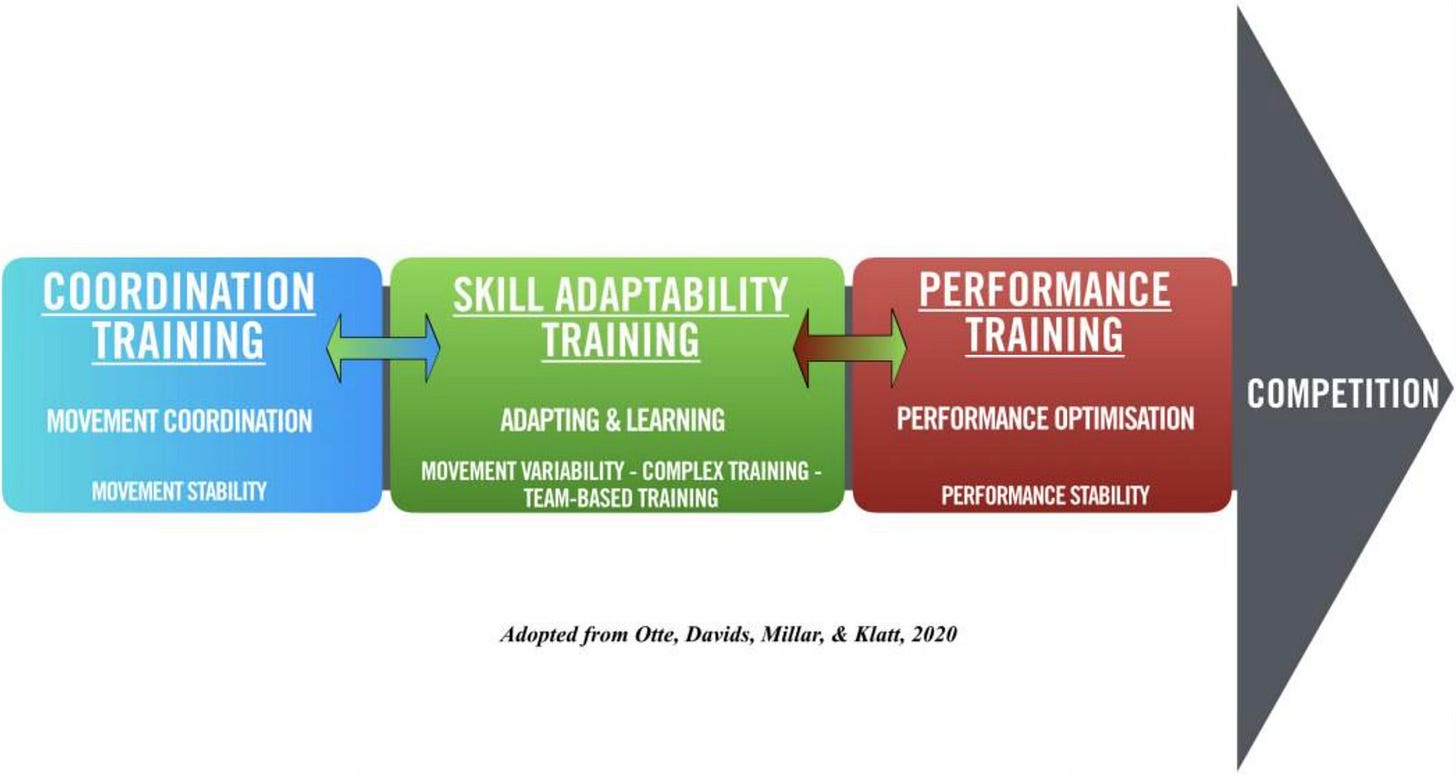

The Three Stages of Skill Development

The research framework identifies three distinct training stages, each requiring a fundamentally different coaching approach:

Coordination Training (learning basic movement patterns)

Skill Adaptability Training (developing perceptual-cognitive regulation in complex environments)

Performance Training (preparing for high-pressure competition).

In the early Coordination Training stage, athletes need opportunities for exploratory activity to perceive novel affordances -new possibilities for action. The primary aim is not to prescribe exact movements but to create learning environments where athletes can discover functional sport-specific actions through simplified tasks.

This aligns perfectly with what I see in business development. Junior employees don’t need a detailed playbook for every client interaction. They need frameworks, a few key principles, and then the freedom to experiment within boundaries. The learning happens through doing, through feeling what resonates with clients, through developing their own style.

During Skill Adaptability Training, the focus shifts to perceptual-cognitive regulation of adaptive actions in more complex and varied environments. Athletes learn to reorganize their perception-action couplings - essentially, how they read situations and respond to them.

In business terms, this is the phase where someone moves from executing standard tasks to handling ambiguous situations, reading room dynamics, adapting their approach based on subtle cues. You can’t teach this through instruction. You can only create rich practice environments and guide their attention toward relevant information.

The Performance Training stage, focused on competitive preparation, is actually the one place where more direct coaching might be appropriate. But even here, the researchers emphasize using it sparingly. Time constraints before important events may require focused, task-oriented communication, but the goal remains supporting the athlete’s self-regulation, not replacing it.

The Practical Methods That Actually Work

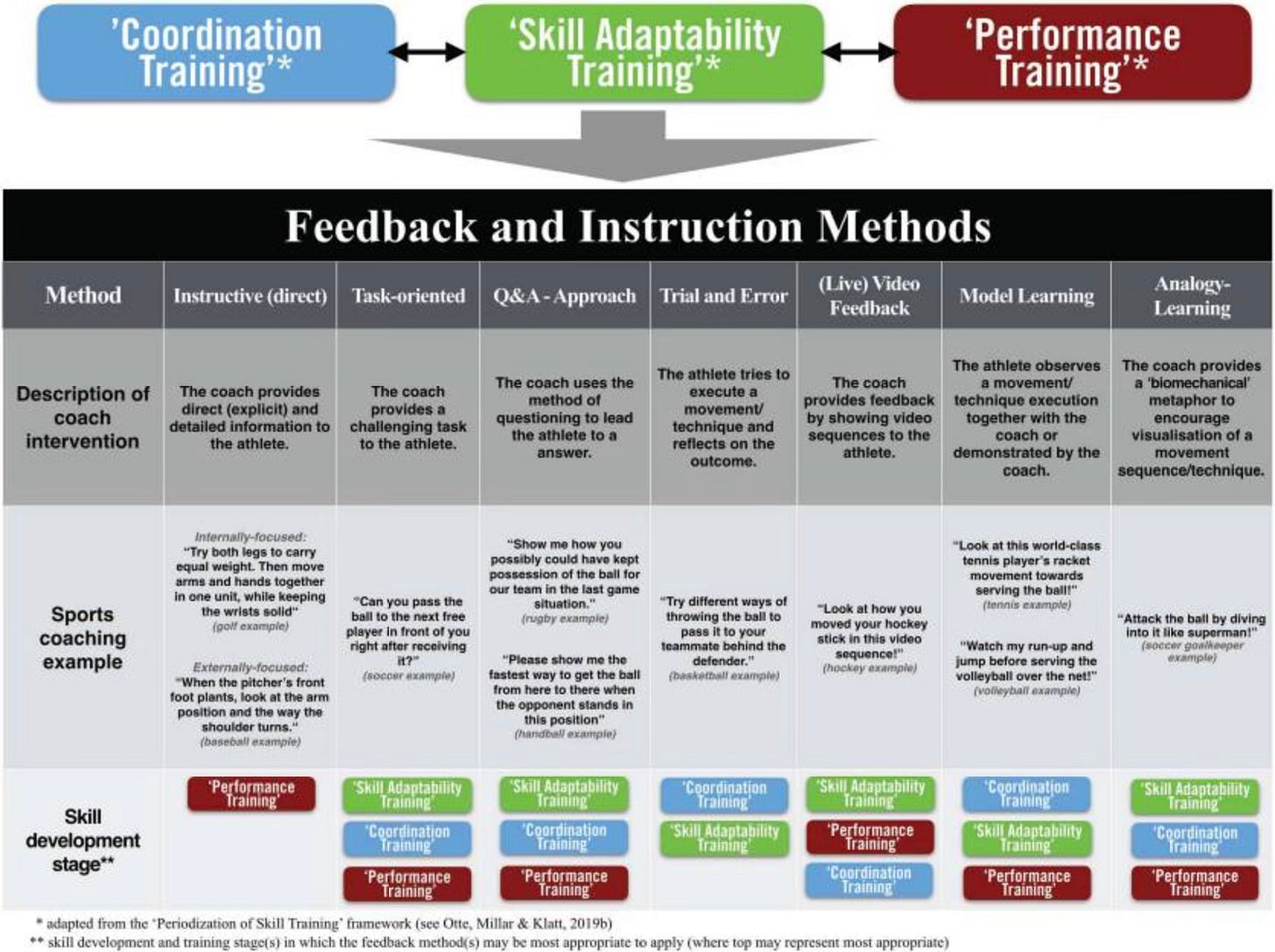

The researchers detail seven distinct feedback and instruction methods, ranging from direct verbal communication to analogy learning. What’s striking is how few situations actually call for traditional prescriptive coaching.

Rather than giving explicit instructions, coaches should use task-oriented challenges: setting a goal without specifying how to achieve it. For example, asking an athlete “Can you open your body toward the full field with your first contact?” rather than “Place your left foot here, angle your body 45 degrees, contact the ball with the inside of your foot.”

The question-and-answer approach is particularly powerful. Instead of telling athletes what they did wrong, coaches ask questions that prompt athletes to discover solutions through their actions, not verbal responses. The goal is to develop “knowledge of” the environment (which supports functional action) rather than “knowledge about” the environment (which is merely symbolic understanding).

Movement analogies - what the researchers call “biomechanical metaphors” - provide another elegant solution. Rather than explicit technical instruction, coaches use verbal illustrations that direct attention externally and promote implicit learning.

For instance, telling a volleyball blocker “your arms and hands build a wall from which the ball bounces back” rather than detailed instructions about arm angles and hand positions.

These analogies are more resistant to forgetting and emotional perturbations because they engage visual imagination and create an external focus of attention rather than conscious control of body parts.

The Overcoaching Trap in Business

The parallel to business leadership is almost exact.

The pattern usually looks like this: A manager sees someone struggling or not performing optimally. The manager’s instinct is to provide more guidance, more detailed feedback, more check-ins. The employee starts relying on that guidance rather than developing their own judgment. Performance becomes adequate but mechanical. The employee stops bringing energy and creativity to their work because they’re executing someone else’s playbook rather than solving problems themselves.

The researchers found that athletes with detailed declarative movement knowledge tend to “choke” under pressure, while those who experienced significant amounts of implicit learning were more resistant to performance breakdowns.

This maps directly onto business. Employees who’ve been over-instructed often freeze in novel situations because they’re searching for the “right” answer they were taught rather than reading the situation and responding adaptively. They lack the self-regulation skills that come from exploration and discovery.

People become dependent, disengaged, less confident. They’re doing the job but not owning it.

The Design Approach to Development

The researchers’ key insight is that the training design itself - the structure of the practice environment should be the main pedagogical method. By manipulating constraints in the environment, coaches can drive exploration and search for functional solutions without having to prescribe movements in precise detail.

In business, this means designing work assignments, client interactions, and projects that naturally surface the learning you want to happen.

For a salesperson developing qualification skills, instead of a detailed qualification script, you might structure their pipeline so they’re handling 3x the leads they can possibly close. The constraint forces them to develop better qualification instincts because they literally don’t have time to chase poor fits.

For a consultant learning to structure recommendations, instead of templates and frameworks, you might assign them to a project with an intentionally ambiguous scope. The constraint forces them to develop pattern recognition for what clients actually need versus what they say they need.

As the researchers note, the training session design aims to be the main stimulus for promoting search, exploration, and learning behaviors. Through constraint manipulation and following the principle of “repetition without repetition,” coaches take an implicit and tacit approach that places dominant focus on training designs supporting expansive search for contextual information.

The coach becomes a designer of practice environments rather than a prescriber of correct actions.

When Direct Feedback Actually Helps

The research isn’t arguing for zero feedback. It’s arguing for strategic, minimal, well-timed feedback that enhances rather than replaces self-regulation.

Feedback timing matters critically. Providing feedback immediately after a performance interferes with intrinsic feedback processing. Athletes need time to perceive information from their own movements before external input guides their attention. Coaches should delay augmented feedback to allow athletes to form their own performance estimates first.

Additionally, low feedback frequency is often sufficient during developmental stages because the focus should be on search and discovery. Less frequent feedback also gives coaches more time to observe athletes’ perception-action couplings and assess training environment quality rather than constantly intervening.

In business, this translates to a “observe more, intervene less” approach during someone’s development phase. Watch them handle multiple client calls before commenting. Let them iterate on a deliverable several times based on their own judgment before providing input. Create space for them to develop their own standards of quality.

When feedback is provided, it should be categorical or graded rather than overly detailed during early and middle development stages: brief cues like “too slow,” “too fast,” “too much spin” rather than comprehensive technical breakdowns.

The Personal Chemistry Factor

The researchers explicitly note that coaching effectiveness heavily depends on personal compatibility. Even experienced and emotionally mature coaches can’t be effective for all athletes. Some need a tough mentor, others respond better to a partnership style. There is no universal approach.

This gets overlooked constantly in corporate environments where we act as if good coaching is a universal skill set. It’s not. Some people thrive under hands-off guidance. Others need more structure. Some want direct challenges. Others need supportive questioning.

The best leaders I know adjust their approach based on the individual, not just their skill level, but their personality, how they process feedback, what motivates them, how they handle uncertainty.

This requires the leader to have strong self-awareness about their own default style and the flexibility to adapt it. A naturally directive leader needs to consciously pull back with people who need autonomy. A naturally facilitative leader needs to provide more structure for people who want clear direction.

The match between coaching style and individual needs matters as much as the coaching content itself.

Implementation Principles

Based on both the research and my experience applying these ideas, here are the core principles:

1. Design > Instruct

Your primary tool is designing the work environment, not providing instructions. Structure assignments, constraints, and feedback loops that naturally surface the learning. Let the situation teach.

2. Delay Your Input

Resist the urge to immediately comment after observing performance. Give people time to self-assess. When they ask “How did that go?”, first ask them what they noticed. Let them develop their own judgment.

3. Ask > Tell

When you do intervene, questions that prompt action are more powerful than instructions. “Show me how you’d handle X differently” beats “Here’s what you should do in X situation.”

4. External Focus

Frame feedback in terms of outcomes and effects in the environment rather than specific behaviors or techniques. “The client seemed confused about our pricing approach” beats “You need to explain pricing earlier in your pitch.”

5. Analogies Over Analysis

When someone needs to develop a new skill, vivid metaphors often teach better than detailed breakdowns. “You’re building a bridge between their current state and desired state” paints a clearer picture for consulting work than a step-by-step methodology.

6. Match Volume to Stage

In early development, minimal explicit feedback. In preparation for high-stakes performance, more targeted input is appropriate. But even then, focus on guiding attention rather than prescribing actions.

7. Personal Calibration

Pay attention to how each person responds to different styles. Some people want you to watch them struggle longer before helping. Others need earlier intervention. Neither is wrong - it’s about the match.

The Confidence Paradox

There’s a paradox at the heart of this approach: giving people less guidance often builds more confidence than giving them more.

When someone solves a problem through their own exploration and discovery, they own that solution. They developed it, they understand why it works, they can adapt it to new situations. The confidence is real because the capability is real.

When someone executes a solution you handed them, even if it works, they don’t feel the same ownership. They’re borrowing your competence rather than developing their own. Under pressure or in novel situations, that borrowed competence evaporates.

The researchers emphasize that a major aim of sports training and practice is supporting self-regulation. The careful application or omission of augmented information needs to consider athletes’ self-regulated exploration and search activities.

This is the real work of leadership development: creating conditions where people build genuine capability through guided exploration rather than dependent competence through heavy instruction.

It requires more patience from leaders. More tolerance for imperfect initial attempts. More time designing practice environments rather than preparing detailed instructions. More observation and less intervention.

But the payoff is people who can adapt, who bring creativity and judgment to their work, who perform well under pressure because they’ve developed robust internal guidance systems.

That’s worth the investment of holding back.