The Shackleton Principle: What Building a Service Business Really Feels Like

About the comfort zone and the ability to create something new from nothing and service companies.

I often recall Peter Thiel’s book “Zero to One” and our recent discussions with colleagues about the comfort zone. Thiel criticizes service companies for their inability to create a monopoly. When we open doors to a new large company, a new market opens up for us, which is also a transition from 0 to 1. A task of comparable complexity is the successful launch of a new practice and technological expertise.

This is a chain of hundreds of events with low probability of success, requiring a very high level of team effort, focus, patience, and faith in success. In IT services, talented people and expertise that is listened to are critically important, as well as confidence that the team will handle the task and successfully complete the project.

In recent years, we have been actively building our brand, and this is starting to bear fruit. In the series of “miracles” based on high focus of efforts, elements have appeared that additionally increase the probability of success. But creating a business “out of thin air” remains a titanic task requiring incredible teamwork and focus.

Often this is not just stepping out of the comfort zone, but constant discomfort and an endless number of negative results, a critically small number of positive events, after which it’s important to maintain faith that you’re on the right path.

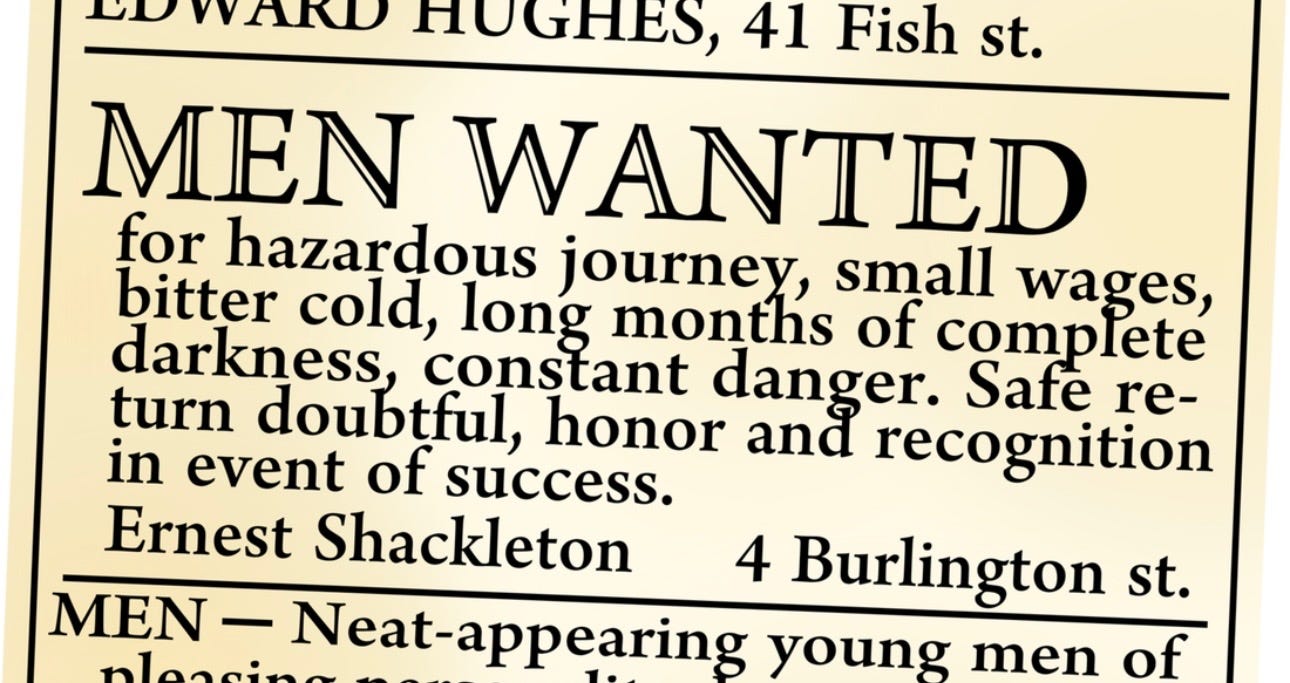

I’ll quote an advertisement that I often remember to illustrate what we had to go through to get a new large contract with a multi-billion dollar company.

“Men wanted for a hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, doubtful return. Honor and recognition in case of success.” - Ernest Shackleton.

This famous advertisement is attributed to Ernest Shackleton before his expedition on the ship “Endurance” in 1914, when he was preparing to explore Antarctica. According to biographical books, a queue of thousands of applicants formed near the office. Although modern historians have not found convincing evidence that such an advertisement was actually published, its spirit conveys the realities of the expedition, during which the ship “Endurance” sank, and Shackleton’s team survived incredible trials. Despite all the difficulties, Shackleton managed to save all members of his team, which became one of the greatest examples of leadership and courage in the history of polar exploration.

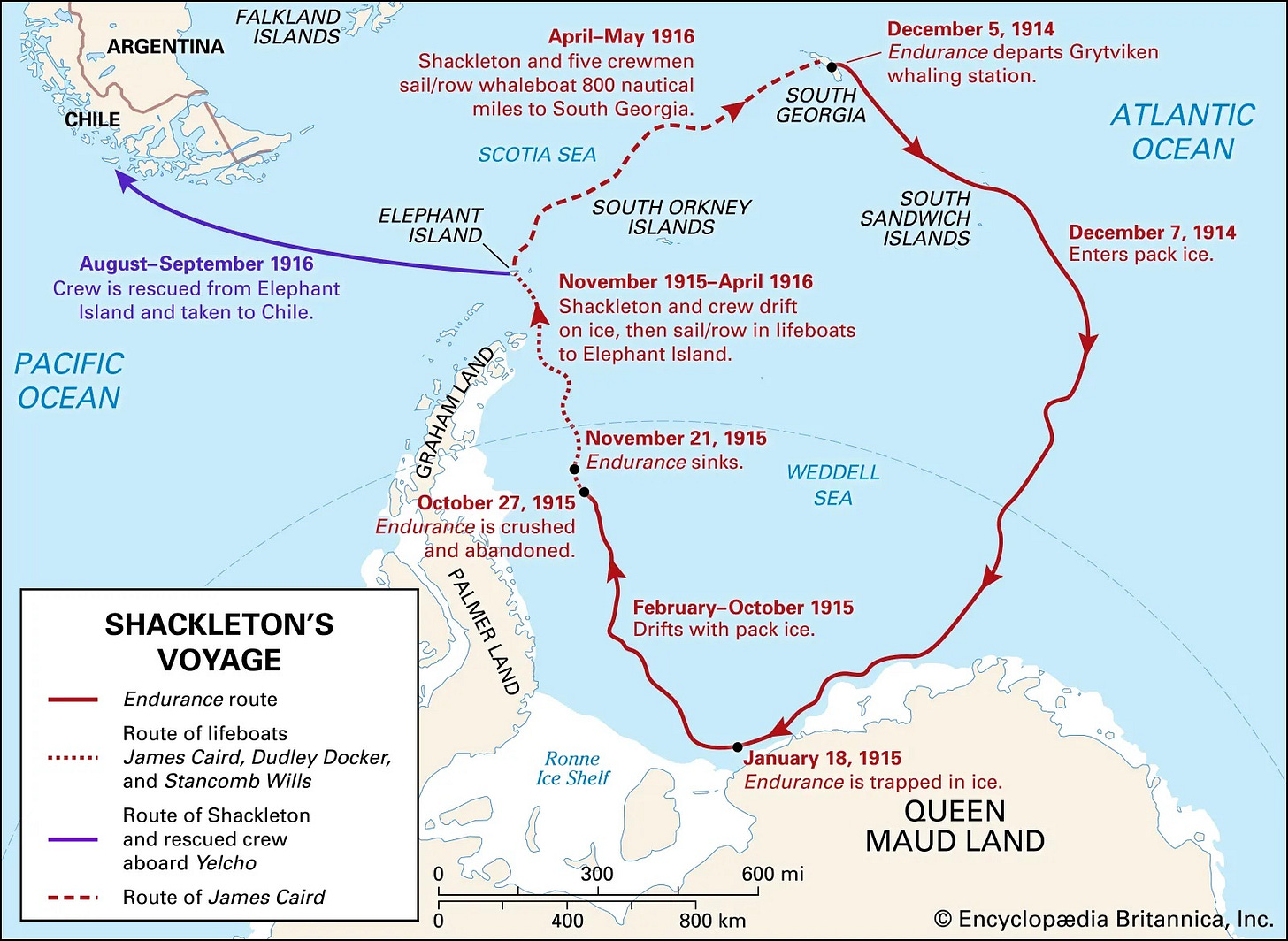

The Chronicle of Endurance

The entire expedition lasted 753 days from departure to the rescue of the final crew members. What’s incredible is that they recently found the ship on the ocean floor and captured it on video - perfectly preserved in the Antarctic waters. One of the crew members was an extraordinary photographer who documented everything, so we have this haunting visual record of what they went through.

Here’s how those 753 days broke down:

August 8, 1914: Departure from England

December 5, 1914: Left whaling station at Grytviken, South Georgia (3 months, 27 days in)

December 7, 1914: Entered the ice (3 months, 29 days)

January 18, 1915: Endurance trapped in ice (5 months, 10 days)

October 27, 1915: Endurance crushed and abandoned (14 months, 19 days)

November 21, 1915: Ship finally sank (15 months, 13 days)

April 9-15, 1916: Launched lifeboats to Elephant Island (20 months, 1 day)

April 24 - May 10, 1916: Shackleton’s open-boat journey to South Georgia (21 months, 2 days)

May 20, 1916: Reached whaling station (21 months, 12 days)

August 30, 1916: Final crew rescued from Elephant Island (24 months, 22 days)

Two years. Nearly two and a half years of constant crisis management, with no guarantee anyone would survive. And somehow, Shackleton brought every single person home.

In our daily life, it’s very difficult to maintain team morale in sales cycles that can last for years, but such is the challenging mission of IT service companies and people involved in sales and marketing.

What Thiel Gets Wrong (And What He Gets Right)

I do get why Thiel dismisses service companies. From the outside, it looks like we’re just competing in existing markets, fighting over the same contracts with the same skills everyone else has. But here’s what he misses: every single client engagement is actually a creative act.

When you walk into a new company, you’re not just delivering a predefined service. You’re solving a puzzle that’s never existed before. Sure, we’ve done “digital transformations” hundreds of times, but this company’s legacy systems, their politics, their culture, their specific regulatory constraints - that combination has never existed in the world before.

It’s the difference between being a cover band and being a jazz musician. Cover bands play the same songs the same way every time. Jazz musicians take familiar standards and create something entirely new in real-time, responding to what the other musicians are doing, what the room feels like, what the moment demands.

Every project forces us to improvise solutions that combine technology, human psychology, and organizational dynamics in ways we’ve never tried before. That’s not competing in existing markets, that’s creating new value in real-time.

The Economics of Surviving on Hope

Here’s the thing about service businesses that nobody warns you about: your most valuable asset literally walks out the door every evening and hopefully comes back the next morning.

All that knowledge, all those relationships, all the hard-won expertise about what actually works versus what looks good in PowerPoints, it’s all stored in people’s heads. And this stuff gets more valuable the more you use it. Every crisis we survive makes us better at surviving the next one.

But building this kind of asset requires surviving periods that feel completely insane from a financial perspective. You’re hiring people you can’t quite afford yet because you know that by the time you actually need them, it’ll be too late. You’re investing in capabilities for opportunities that might not exist for years.

I’ve watched so many service companies kill themselves by optimizing for next quarter instead of next year. They take any project that pays the bills, even if it teaches them nothing and positions them nowhere. They stay busy instead of getting better.

When Everything Clicks (Finally)

There’s this magical moment that happens if you survive long enough. Clients start calling you not because they know exactly what they need, but because they trust you to figure out what they don’t even know they need yet.

This is when all those years of uncertainty finally pay off. You’re not competing on price anymore because there’s literally nobody else who can solve this specific type of problem. Your proposals aren’t just about what you’ll do, they’re about helping clients understand what’s actually possible.

But getting there requires the kind of faith that feels borderline delusional. You have to believe that all this expertise you’re building, all these relationships you’re nurturing, all these capabilities you’re developing, they’re going to compound into something unique and valuable. Even when you’re six months into a sales cycle that might go nowhere. Even when your best people are getting recruited by companies that can pay them more right now.

The expertise monopoly is different from other kinds of monopolies. It’s not about controlling supply or blocking competitors. It’s about becoming so good at solving a specific type of complex problem that clients would rather wait for you than hire someone else immediately.

The Leadership Challenge Nobody Talks About

Managing a service business through the long cycles is its own kind of psychological experiment. You’re asking talented people to maintain peak performance while dealing with constant uncertainty about when the next big contract will close.

Unlike product companies where you can point to users or revenue growing every month, we often go long stretches where progress feels invisible. You’re building capabilities that might not pay off for years. You’re nurturing relationships that might never turn into business. You’re positioning for opportunities that might not exist yet.

Your team needs to stay sharp and motivated while working on proposals that have maybe a 20% chance of closing. They need to keep learning and growing even when it’s not clear how that investment will pay off. They need to believe in the vision even when the monthly numbers look terrifying.

I’ve learned that the best service company leaders aren’t the inspirational visionaries you see at startup conferences. They’re more like expedition leaders - helping people find meaning in daily problem-solving while maintaining absolute conviction that the capabilities we’re building will create exceptional opportunities.

Some months, honestly, it’s just about helping everyone remember why we chose this particular form of professional adventure.

When “Failures” Turn Into Foundations

Here’s something about Shackleton that always gets me: by conventional measures, his most famous expedition was a complete failure. He never reached his destination. The ship was destroyed. They spent two years just trying to survive.

But that “failure” established his reputation and enabled everything that came after. The leadership he demonstrated during the crisis became the foundation for future opportunities he couldn’t have imagined.

Service businesses work the same way. Projects that feel like disasters often generate the relationships, capabilities, and credibility that enable breakthrough successes later. The key is maintaining enough perspective to recognize when apparent setbacks are actually investments in future capability.

The question isn’t “Will this project be profitable?” It’s “Will this project make us more capable?” Sometimes the answer is yes to both. Sometimes you have to choose. But the companies that survive long enough to build something exceptional are usually the ones willing to make strategic bets on their future capability, even when it’s expensive in the short term.

Thanks! It’s interesting to read. How did you start your service business? How did you get your first client?

Also interesting to read about marketing channels which you are building if this is possible to share